Elisabeth Freeman had returned to England with her mother, supporting themselves by making silk ribbon flowers for nobility. She tells the story of her conversion to the suffrage cause this way: “I saw a big burly policeman beating up on a woman, and I ran to help her, and we were both arrested. I found out in jail what cause we were fighting for.”

Elisabeth found a cause that so uplifted her and saved her from the tedium of daily life that she likened it to spirituality: “But the supreme spirit of the militant movement is one that, I say reverently, is not of this world. In the great battle of Downing Street, as I looked down the line of marching women I saw that their faces were turned to heaven, and there was that expression which awed and uplifted me. It was as though the early Crusaders had been reincarnated in them. I felt that I was watching the advance of a mighty Christian army.”

- At a demonstration, a woman in a bath chair urges women to “join the next deputation” to bring the demand for woman suffrage to the government

- Elisabeth Freeman with French delegation at large suffrage parade

She threw herself into the cause, being arrested nine times, and eventually serving two (or more) terms in dreaded Halloway Jail where suffragettes* went on a hunger strike and were force fed. She earned a “medal of honor”, a pin depicting a prison gate, and wore it proudly.

* The WSPU took the more radical term “suffragette” whereas the more socially acceptable term was “suffragist.”

- Brochure from event honoring suffragettes who went to prison for the cause.

Left: WSPU honored the women who sacrificed themselves by going to jail with a small pin in the shape of a prison gate with the v-shaped arrows denoting prisoners garb.

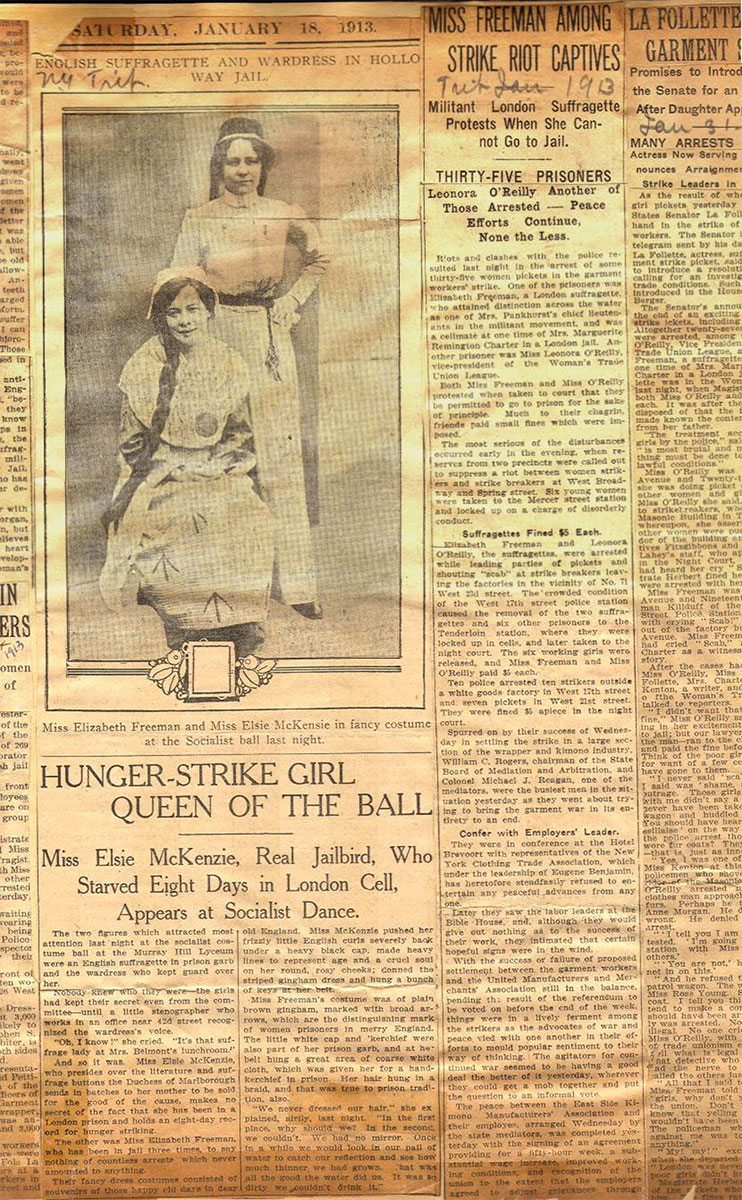

Right: Elisabeth at a costume ball dressing as a suffragette prisoner. Note “arrows” on skirt, denoting prisoner

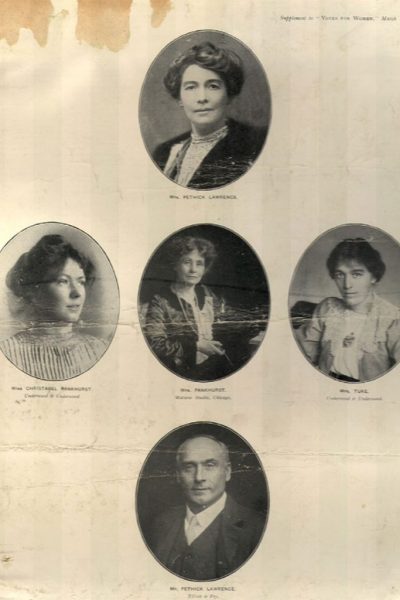

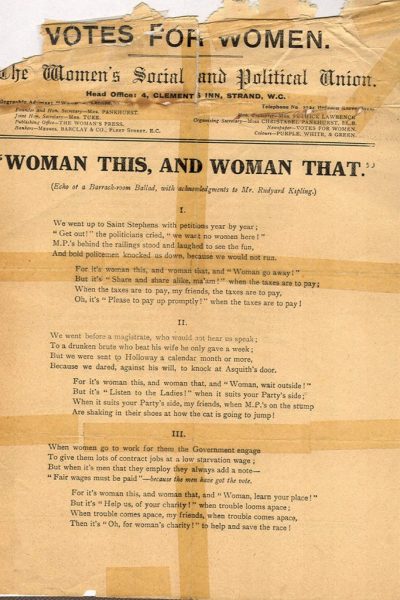

Emmeline Pankhurst, with her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a militant suffrage organization. In the English Parliamentary system it is customary to target the Prime Minister and the party in power to effect change. Members of the WSPU were fiercely loyal to the Pankhursts who ran the organization like a military operation, with escalating militancy. They sponsored several “deputations” (large delegations with demands in hand) to the Prime Minister or Parliament and were inevitably met by police and arrested before getting to the gates. The song Woman This and Woman That describes the need for such tactics.

- Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence, Treasurer (left under banner) and Christabel Pankhurst, chief strategist of the WSPU at a demonstration

- WSPU Leaders

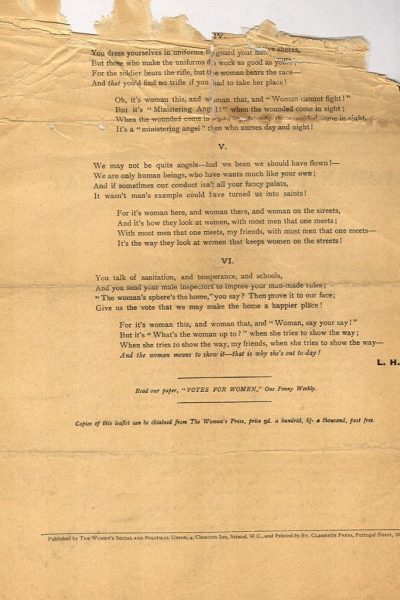

- “Woman This and Woman That” is a parody and song explaining why the WSPU had to resort to their militant tactics, “with apologies to Rudyard Kipling”

- “Woman This and Woman That” is a parody and song explaining why the WSPU had to resort to their militant tactics, “with apologies to Rudyard Kipling”

The WSPU also sponsored huge processions and rallies with elaborate pageantry to capture the public imagination. Eventually, they relied on daring “stunts” like hiding a suffragette in the rafters of a hall where there was to be a meeting and then calling out “Votes for Women” to the dismay of the party leaders. Their later tactics escalated to breaking windows, setting fire to post boxes, and other acts designed to disrupt the government until it gave in. They finally negotiated a “ceasefire” when England went to war with Germany; the WSPU offered their disciplined “troops” for the war effort in exchange for the vote after the war.

On the envelope, EF scribbled, “I went anyway.” and “Normally, no thanks were given.”

Elisabeth found an outlet for her passions and learned the discipline and tactics of the British suffragettes. She went on several deputations and was arrested nine times, according to one account. She also apparently worked hard to engage others. She sold suffrage papers in Trafalgar Square and organized the American and foreign contingents at one of the large demonstrations. She also was one of the speakers at Hyde Park. Although there is no evidence that she got paid for her work, she gained the necessary skills and confidence to market her abilities in the U.S. When she returned to the America, she used her militant training as a badge of honor and a gimmick to obtain speaking engagements and guaranteed press coverage. She kept some connection with English suffragettes as Mrs. Pethick Lawrence sent her a statement for a meeting in New York City. The sacrifice of oneself to the movement forged a new definition of femininity–genteel yet fearless, self-sacrificing not just for husband and children but for the uplifting of women, and by extension, all of humanity. With this fire burning within, Elisabeth Freeman was able to overcome a predisposition to feeling ill, to endure all hardships, and to wax eloquent from soapbox and stage alike.

Elisabeth Freeman Collection courtesy of Peg Johnston

- Parade on the release of Miss Phillips, leader of the Scottish suffragists. Mrs. Pankhurst is on the left, next to her, holding the rope.

- Joan of Arc depicted in a parade

- Women costumed as "voteless" famous women

- This photo of a demonstration at a by-election is labelled "forcible advert", a street demonstration for votes for women

- Photo of crowds from stage, Elisabeth Freeman Speaker

1905-1911 London: The Making of a Militant Suffragette Additional Information

Dress Up

Who doesn’t love playing dress up? Well, me for one, but not so our heroine Elisabeth Freeman. She loved fancy dresses and used her fashion sense to draw attention to her cause. Take the “Pilgrim’s Hike” from NY to DC in February 1911 to join the Women’s March the day before Woodrow Wilson’s Inaugural. (Talk […]

Suffrage Jewelry

Following up on the Wishbone Ring, my cousin asks if there was other “suffrage jewelry.” I’m sure there were lots of cloisonne pins and of course buttons, which might count as jewelry in my wardrobe. But the most prized piece was that presented to English suffragettes who had done prison time for their beliefs. It’s […]

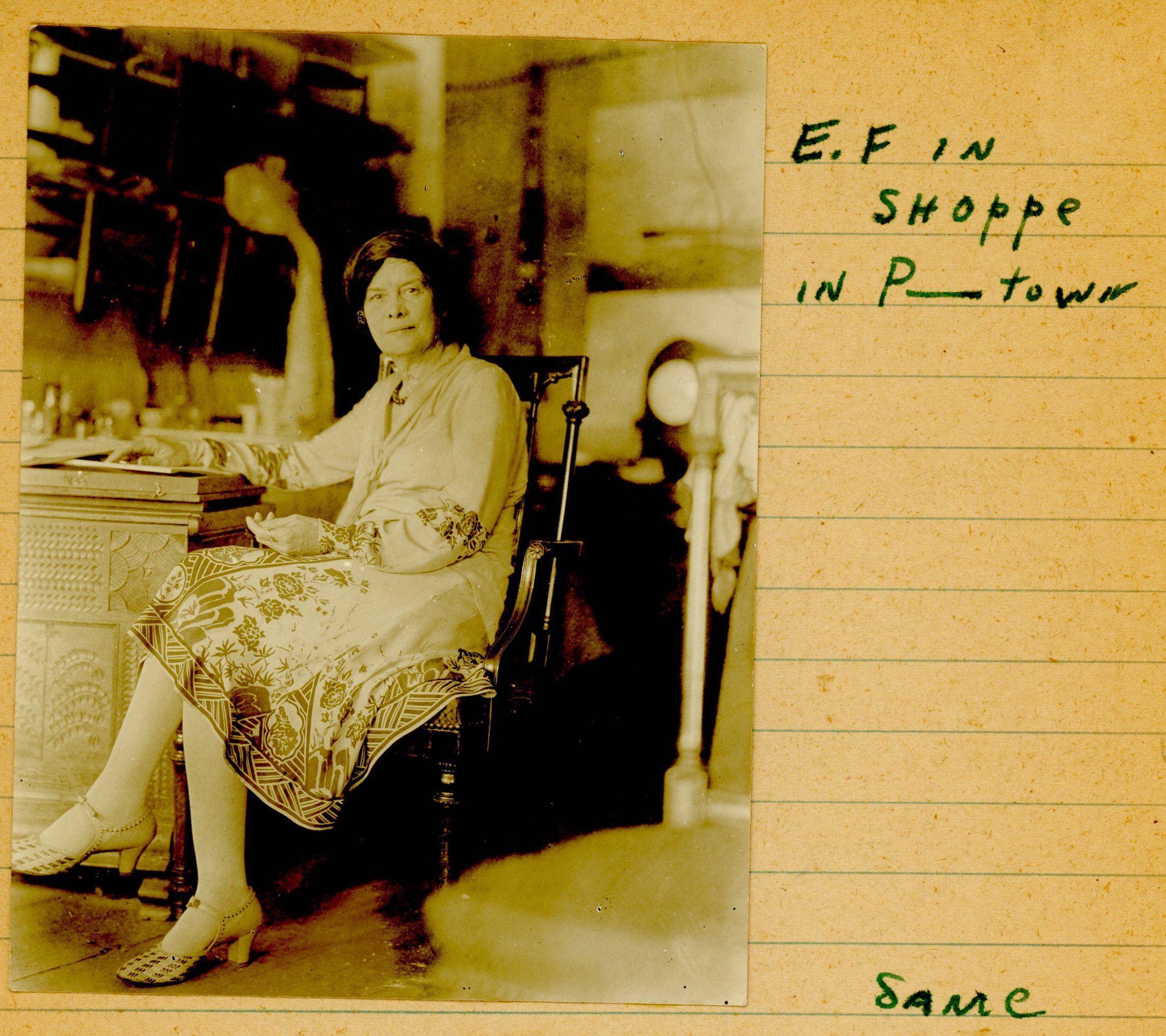

The Wishbone Ring

A side line of Elisabeth’s–and every freelance activist needs a second gig–was selling antiques. When she was on the road, she carried some watches to sell. One specialty was seriously old pocket watches (the size of a baseball), and also creating rings out of the ornate watch cocks from fancy watches. Elisabeth had a store* […]