In the presidential campaign of 1916, Charles Evans Hughes challenged President Wilson who had not supported suffrage for women, in spite of the demonstration at his first inaugural in 1913. (see “hike”) Frances Kellor, who organized the Women’s Campaign Special, was active in Teddy Roosevelt’s 1912 campaign and believed that educated women could bring their expertise to social problems. The train was a novel way to use talented women in a political campaign, putting to rest the notion that politics was “too dirty” for women. Kellor contacted Elisabeth Freeman about a speaking engagement while she was still on a speaking tour for the NAACP.

The “Hughsettes” as they were sometimes referred to, made political history; this was the first time that a party had committed to using women in such a visible way. By the time their criss-crossing the country was done they had spoken in 28 states, travelled 11,075 miles, and “given 1,840 speeches, indoors and out, in circus tents, coliseums, movie palaces, and street corners.” Kellor assembled an impressive collection of women, balanced in terms of old guard Republicans, progressive activists, and prominent women of the day. Notable on this list were Mrs. Maud Howe Elliot, daughter of Juliet Ward Howe, Mary Antin, immigrant rights worker, Mrs. Raymond Robins, a labor leader, Dr. Katherine Davis, Commissioner of Corrections, NYC, Rheta Childe Dorr and Ernestine Evans, journalists embedded on the train, and Mrs. O’Shaughnessy, wife of a diplomat to Mexico.

Elisabeth Freeman spoke to black audiences and also on the subject of suffrage and labor to white and black audiences. The train attracted huge crowds and gave GOP women the facts and arguments to campaign for Hughes locally. But, as the train traveled west the opposition–Democrat supporters– became better organized and met campaign events with hostile newspaper ads, jeering, and even violence.

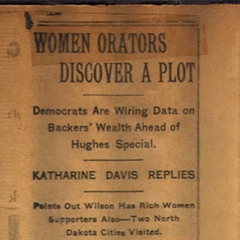

A smear campaign accusing the women on the train of being “the idle rich” thus undermining their appeal to progressives and the working class, was particularly effective and the women speakers had to respond to these accusations. In fact, the assembled speakers on the Campaign Special were from all walks of life—and work—but the epithet “The Golden Special,” for the wealth of some of its speakers, stuck to them.

Elisabeth was featured prominently in some accounts and her proven track record in street speaking, extemporaneous oratory, and handling heckling made her especially useful. Although she spoke to black audiences and on suffrage topics, she was not above partisan jibes at President Wilson himself, accusing him of “flopping on issues.” She seemed to specially endear herself to the cowboys in Miles City Montana, two of whom corresponded with her later.

Teddy Roosevelt backed Charles Evans Hughes as did other progressives and Woodrow Wilson himself thought that he might lose to Hughes, but the growing fear of war influenced voters to vote for Wilson on the grounds that “he kept us out of war.” In the aftermath of the election many pundits analyzed the role of the women campaigners in the outcome and Elisabeth herself wrote a letter to the editor about the Hughes Women’s Campaign Special. Frances Kellor wrote an article in the Yale Review, “Women in the Campaign” which was re-printed as a brochure, concluding that “women will become an increasingly important factor in national elections…”

1916 Hughes Women’s Campaign Train Additional Information

Cowboy Hospitality

On Board the Women’s Hughes Campaign Train, 1916 Imagine, if you can, a cross-country–both ways– train trip with a bunch of elite women, stopping several times a day to campaign for the Republican presidential candidate. OK, you probably can’t imagine because it was 1916 and the Republicans were the “good guys” in favor of women’s […]