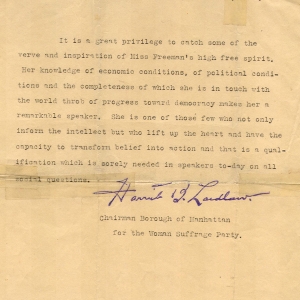

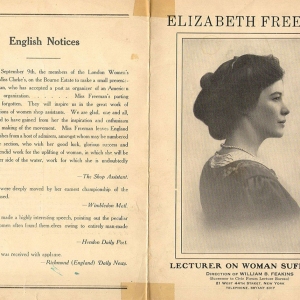

By many accounts the American suffrage scene desperately needed an infusion of energy and starting in 1909, many English suffragettes found a role to play in the U.S. The power structure was completely different, however: in America, each and every voter—male voters, except in some Western states where women had the vote—was important and both personal contact and press coverage were crucial to revitalizing the movement. Similar to England, this translated to street speaking, public lectures, and pageantry (referred to as “forcible advertising” in England). Elisabeth seemed particularly adept at getting the attention of the many newspapers in existence.

To Elisabeth, who had gone to jail for the Cause, street speaking, selling suffrage newspapers, and attracting the attention of reporters and photographers were child’s play. However, she eventually found the apathy of American activists quite appalling. (see Woman’s J letters) As the copious press clippings attest, Elisabeth Freeman knew how to charm “the media” and she also managed to charm press photographers into giving her original prints. Even when the press was against them, she knew that suffrage was being discussed at the dinner table.

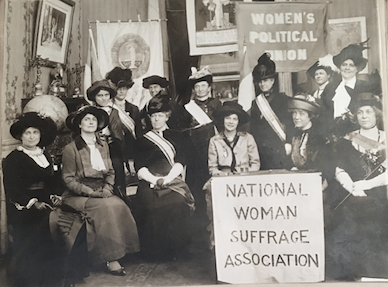

Elisabeth Freeman was represented by Wm. B. Feakins Speaker’s Bureau and also worked with many of the suffrage organizations of the day, including the NYS Woman’s Suffrage Assn., the Women’s Political Union, the National Woman’s Suffrage Assn., The Woman’s Journal, the Texas Woman’s Suffrage Assn., and the Congressional Union. In addition to platform speaking, she was known for her “media stunts,” finding some activity that would capture media attention and guarantee press; in some cases this was an attempt to “piggy back” onto another story as in volunteering to pick up garbage during the NYC garbage strike and sometimes creating their own event. On several occasions she spoke between rounds of a prize fights, at the movies or theater, and at state or county fairs.

Elisabeth was also an ardent supporter of women trade unionists, and labor issues were among her speaking topics. She supported the striking garment workers, getting arrested with them, and was one of the speakers protesting the famous Triangle fire, a factory that burned down with many women locked inside. Elisabeth received a great deal of press coverage when she protested at Standard Oil with Upton Sinclair, over the oil company’s shooting of striking miners in Colorado.

Elisabeth was involved with the NY City Suffrage Assn. when she first returned to the US and had several speaking engagements and road trips throughout the Metropolitan area. She also joined other suffragists in lobbying Albany, the state capital and later did a walking tour from NYC to Albany.

In the summer of 1912, Rosalie Jones and Elisabeth Freeman took their campaign to Ohio with a little yellow wagon filled with literature. Said Jones, “We could have driven in an automobile but then we wouldn’t have to stop so often” and would miss opportunities to talk to farmers and people in small towns. Rosalie was the organizer and Elisabeth was the speaker for the campaign; in every town and crossroad, she would speak on the street and try to schedule a meeting for the evening. As in other stunts, a good deal of publicity was given to the horse and wagon, which they named “Suffraget.” This stunt was physically demanding and the pair frequently slept in their wagon over night and ate their food in the open air. In the end, the anti-suffrage forces were well organized and Ohio did not go for suffrage.

The most arduous media stunt was the “Suffrage Hike” or “pilgrimage” to Wilson’s first Inauguration in the winter of 1913. Again, organized by millionaire heiress Rosalie Jones, the hike coincided with a large parade that Alice Paul of the more radical Congressional Union (of the HBO special “Iron Jawed Angels”) was staging to confront Wilson and Congress on the issue.

Elisabeth was engaged to be the official speaker on the trip and drove the literature wagon. She was dressed as a gypsy, a traditional follower of “pilgrimages” and she offered to read palms and tell fortunes as a way of attracting a crowd. The stunt garnered full page coverage in every town along the way, but at great physical and emotional cost. The women arrived in Washington DC exhausted and discouraged, and were a fairly insignificant part of the giant parade which attracted sometimes violent detractors. Still, the hikers engaged the public, causing much excitement, especially among students.

The Congressional Union differed from other, more conservative groups, by bringing British logic and techniques to America. They eventually picketed the White House in an attempt to hold the party in power accountable for suffrage. This contrasted with the slow state by state method of appealing to voters favored by the major suffrage associations. Ultimately both methods were needed since the suffrage amendment needed to be ratified by each state.

In 1914, Elisabeth was engaged to take a horse drawn carriage trip from NY to Boston complete with hurdy gurdy (a music machine) to gather a crowd. The Woman’s Journal, the oldest U.S. suffrage paper, founded by Alice Stone Blackwell sponsored the trip. An intact correspondence with Agnes Ryan of the Journal reveals their media savvy and political intrigue. (Note: These letters have been transcribed to resemble actual letters due to poor copies.) Their strategy was successful in getting newspaper coverage, some of it negative, and some of it chronicling their attempts to engage officials in the cause.

Elisabeth was also engaged to hike through Sullivan and Dutchess Counties NYS with an oxen team, as a paid organizer to tour upstate New York, especially centering her efforts in Syracuse NY. In 1916, she was engaged by the Texas Woman Suffrage Assn. to make a tour of that state and enliven suffrage supporters. Her impressions of the Texas scene were captured by several letters to her mother. Elisabeth left that post after investigating the lynching for the NAACP, and under contentious circumstances.

19011-1916 Media Stunts Blog Posts Additional information

Filling In the Gaps

Book Review: “Rosalie Gardiner Jones and the Long March for Women’s Rights” (McFarland) By Zachary Michael Jack Even with my hundreds of clippings of the “Pilgrim’s March” in March of 1913, there are always gaps in our understanding. In the Elisabeth Freeman collection there are precious few personal references that would help us understand how […]

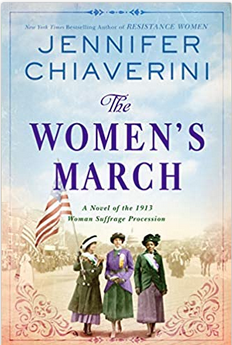

The Women’s March: A Review

I love fiction. Historical fiction is one of my favorites and I suspect that a lot of people get their history facts from these books. The good thing is that most historical fiction authors are pretty good about sticking with the facts although they make up dialogue and personalities, hence the fiction. But if you […]

Dress Up

Who doesn’t love playing dress up? Well, me for one, but not so our heroine Elisabeth Freeman. She loved fancy dresses and used her fashion sense to draw attention to her cause. Take the “Pilgrim’s Hike” from NY to DC in February 1911 to join the Women’s March the day before Woodrow Wilson’s Inaugural. (Talk […]

EF in the Talkies

Talk about Elisabeth Freeman as a footnote in history!! Thomas Edison was perfecting the first “talkies”–film and sound recordings synced. Casting about for a popular topic he turned to Votes for Women, which was then most controversial. Freeman’s mission was to generate so much awareness of the cause that it became dinner time conversation in […]