The Women’s March: A Review

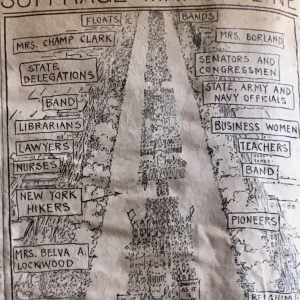

Jennifer Chiaverini has the reputation of being someone who sticks with the facts but makes the characters come alive for us. Her book, The Women’s March– A Novel of the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Procession is about the Suffrage march in 1913, which upstaged President-elect Wilson’s inaugural and made it clear that the suffrage issue could not be ignored. In reading it, I found myself wondering what was fact and what was fiction, and what her sources were. She did not footnote her sources, which would not be typical in a work of fiction, but a note on sources would have been helpful.

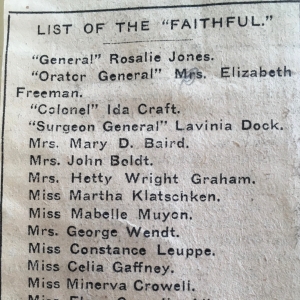

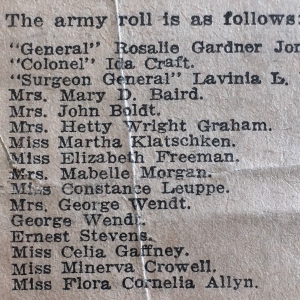

Chiaverini did reveal one plot invention that allowed her to tie together her three heroines—Alice Paul founder of the Congressional Union and mastermind of the March; Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the anti-lynching journalist, civil rights worker, and black suffragist from Illinois; and Maud Malone, a disruptive figure from NY who persisted in asking politicians of all stripes what their position was on woman suffrage. In the book, Maud is one of the hikers with General Rosalie Jones. The author acknowledges in the book’s afterword that Maud Malone “probably wasn’t” on the Pilgrim’s Hike from NY to DC in the cold month of February 1913.

Elisabeth Freeman, was on that hike, every muddy inch of it

Our heroine, Elisabeth Freeman, was on that hike, every muddy inch of it, and like Maud Malone she was an outspoken speaker willing to shake up the usual social order to speak out for suffrage and other causes. This blog has been mining her giant scrapbook of newspaper clippings and memorabilia; the Pilgrim Hike and Women’s March were the most detailed of any of her activities. (As an aside, Maud Malone does show up in the clippings in Upton Sinclair’s protest of Rockefeller’s massacre of striking miners.) In looking through the many pages of clippings about the hike I found a few interesting references to the questions raised in the book.

The infighting between “General” Rosalie Jones and the mainstream suffs is fascinating and was real enough, but I would love to know more background. The center of the controversy was a letter from Dr. Anna Howard Shaw President of NAWSA. Rosalie had requested that she write a letter to President-elect Wilson, which they would deliver. The closer they got to Washington politics, the less the optics of that seemed like a good idea. So NAWSA HQ instructed Rosalie to hand the letter over to Alice Paul, head of the Congressional Committee for delivery, sparking a fight in the newspapers. In the end, no meeting with the President happened, although the largest demonstration surely had more of an impression on him than the rather timid letter would have.

Gen. Jones, for her part, stated that the letter was the reason for their hike (which it wasn’t) and that national was just “jealous” of the publicity she was getting (which was the point–the phenomenal coverage). Genevieve Champ Clark, daughter of the Speaker of the House, wrote her version of events and said, “Before I came upon those heroic women…I had regarded the hike as sort of a lark.”

Chiaverini seems to imply that national and Paul thought the Hike was ill-advised and perhaps a “distraction” created by rogue players. Paul was right that “message control” was vital. I can’t imagine a national event of this magnitude today being upstaged by a handful of unaffiliated partisans. If you’re going to stage a giant protest you want a united front. But the hike provided front page suffrage copy for the better part of a month in the dailies. And as Col. Ida B. Craft always pointed out, the person to person contact won many converts to the cause.

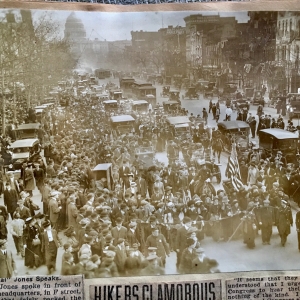

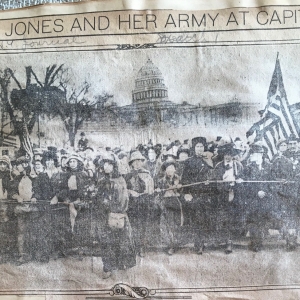

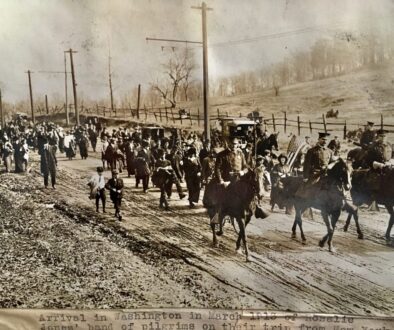

“It was a bitter little band of brave women, who walked with heads erect from Fifteenth and H Streets NE to the Capitol and then through Pennsylvania Avenue,” wrote one paper. The hikers, however, were enjoying the large crowds cheering them on when, at 12th St., two women, “attired as heralds in white, dashed up on snow white steeds. They said nothing to the ‘General’ … but immediately took the head of the line.” Alice Paul showed up and mollified the hikers with a warm welcome. Still, some of the hikers skipped the luncheon honoring them. (“Hikers are Vexed at Suffragettes” Feb 28, 1913; also “Public Greeting is Balm to ‘Hikers’ on Entry to Capital” both unidentified newspapers) The picture here shows the police escort and the two heralds and Elisabeth’s little wagon surrounded by a sea of people.

A nice touch from The Woman’s March is the loyalty of the press corps embedded with the hikers. There were 16 “war correspondents” covering the hike at one time or another and they were unusually loyal and protective of the hikers, so the idea that Rosalie could have insisted that they march with the hikers is plausible, but that they fended off violent crowds is open to question in my mind. And would have these embedded journalists have joined the March? Again, I’d love to see documentation of that, even as I admire the flourish.

(One clipping suggests that the journalists were “advisors” to Jones, and clearly wished her to start another organization but Jones repeatedly said, “I’m a soldier and will follow orders” although that didn’t stop her from being publicly grumpy about it.)

Troublesome part of suffrage history

The most compelling character in The Woman’s March is Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the black woman who challenged the white suffragists to allow Negro Women’s Suffrage clubs to march. In the book, “national” is trying to appease the Southern chapters who threatened to pull their support if blacks were allowed to march, so they waffled about black participation. Alice Paul was a Quaker so it is quite likely that at first she welcomed Negro participation before national politics came into play. This is one area where some real documentation would illuminate this troublesome part of suffrage history.

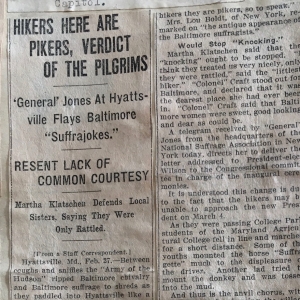

As for General Jones, we have a less than stellar response on the issue. At the end of an article about how Baltimore suffs were not willing to hike with the Pilgrims, there is a short item “Negro Women May Join” which I quote in its entirety, to show the racism of the news writing at the time as well as her response:

“There is a cloud over the cause of suffrage and gloom in the hearts of the hikers this morning, owing to the threatened coalition with the army of the ‘emancipated sistahs’ at Hyattsville. The tip is warm that the colored contingent will ‘jine de ahmy’ at Hyattsville and that no amount of persuasion will deter them from their purpose.

‘General’ Jones has declared flatly that she does not believe the report, but she says that if the dusky champions of suffrage enter the hikers’ legion there will be no strong objection.

‘We cannot with dignity force them to stay out if they desire to follow us into Washington, and I think it is wise to make the best of the situation and leave them alone.” (“Hikers Here Are Pikers, Verdict of the Pilgrims, ‘General’ Jones at Hyattsville Flays Baltimore ‘Suffrajokes’” n.d. but probably Feb 28, 1913, unidentified newspaper.)

Jennifer Chiaverini’s The Women’s March is definitely worth a read, even if, or actually because, it prompts questions. As a work of fiction from a best-selling author, people will read it and get inspired to know more about this incredible piece of history. Thankfully, this footnote in Suffrage history will get noticed.

PS: And if you have info to share, please contact me.