In early 1916 Elisabeth Freeman was hired by the Texas Woman’s Suffrage Association to make some inroads there. On the long train trip down to Texas, Elisabeth met Roy Nash who was working on an anti-lynching effort for the NAACP. The NAACP leadership felt that they needed a well documented case of lynching to raise a public outcry about the practice. The NAACP was founded in 1909 and needed a high profile issue to build membership.

Elisabeth criss-crossed the state for suffrage on a contract that would last 3 or 4 months. On May 16th, Roy Nash wrote a letter asking Elisabeth to investigate the lynching of Jesse Washington, a young man in nearby Waco: “Will you not get the facts for us? Your suffrage work will probably give you an excuse for being in Waco…” Elisabeth was on the scene soon after it happened and interviewed everyone from the judge and sheriff to the family of the young man as well as the family of the woman he was accused of killing. She spent about a week there interviewing people, getting photos of the event, and trying to locate people to protest the lynching. She also visited black churches in town and apologized for the behavior of whites.

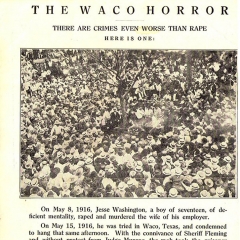

Apparently there was no real doubt about Washington’s guilt, but the fault lay in the security of the courtroom. Just after the verdict, a mob grabbed him and dragged him around town, tortured him, and burned him alive while an estimated 10,000 people watched. A photographer was forewarned and set up near the lynching site, capturing it all on film.

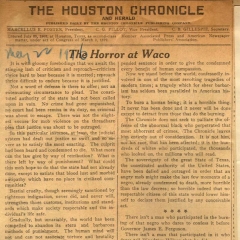

This was the perfect case for the NAACP—solid intelligence by an outside observer, photos documenting the horror, and a town that was not a “backwater” place, but a young city with dozens of churches, several colleges, and a modern outlook. The NAACP used this information to launch their anti-lynching campaign, and to raise awareness and funds for this effort.

Elisabeth used all of her wiles and intelligence to investigate the situation. She flirted to get what she wanted and bravely confronted officials and citizens alike, at some danger to herself. Her hotel room was searched twice and she herself was told to “get out of town before you are hanging on that tree.” * Elisabeth was outraged by this lynching and threw herself into this new cause. The blatant injustice and cruelty of the case fueled her keen sense of social justice. (For a thorough narrative of this case and Freeman’s investigation read the First Waco Horror by Patricia Bernstein www.patriciabernstein.com)

Her report led to two national speaking tours on behalf of the NAACP and its Anti-Lynching Campaign Fund and to another cause in her career. Her work for Texas suffrage came to an abrupt end although this may have been unrelated to her controversial anti-lynching work. She was particularly dismayed that even liberal Texans seemed unwilling to bring a legal challenge against the leaders and the officials in Waco.

Her speaking tours over the course of the summer of 1916 brought her into new territory. (itinerary-naacp) As a suffragist she was used to coming into a town in the morning, meeting suffrage sympathizers, speaking on the street, and being invited to speak in the evening at a meeting or other gathering. This same tactic was not always successful in the Negro communities where she was trying to organize. Undoubtably black communities were much more cautious about their organizing efforts. Speaking events and meetings were announced by small cards, circulars/posters, and announcements in the black press; the NAACP also used direct mail and brochures to detail their campaign against lynching. Still, she managed to raise money and awareness and to get much needed tactical information for the NAACP. She also met several members of the black women’s movement, notably Mary Talbert, a leader in the NAACP and the Nat’l Assn of Colored Women, women in the National Assn of Teachers in Colored Schools, and others.

Elisabeth seemed at ease among this new audience who admired her “pluckiness” in investigating the lynching and speaking out about racial injustice. Women’s suffrage groups, which were largely white, and black organizations did not always see eye to eye, as this exchange between two groups in Ohio illustrates: “…to them (black men) the ballot in the hands of white women appears only in the light of an increased number of civil and political oppressors,” wrote a representative of the women of the Columbus branch of the NAACP.

Elisabeth’s new cause did bring her to the attention of Frances Kellor, who organized the Hughes Women’s Campaign Special, as well as other more radical groups.

* Interview with Freeman’s niece, Ruth Freeman Johnston, 2004.

1916 NAACP Anti-Lynching Campaign Additional Information

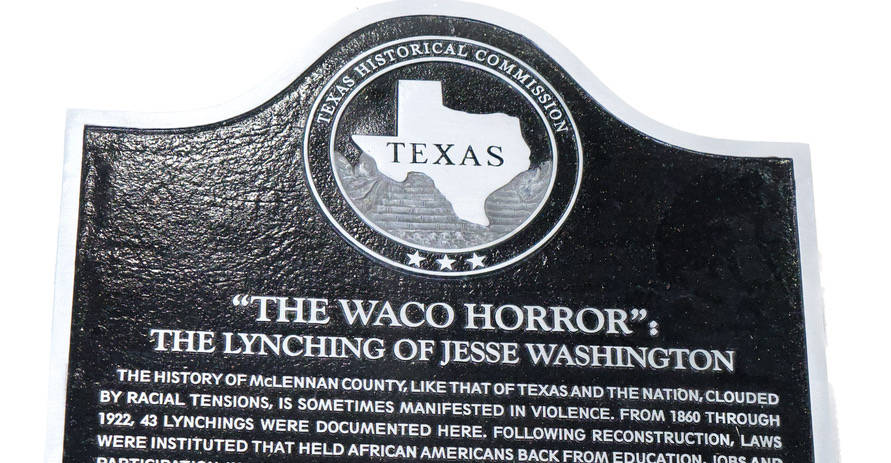

Historical Marker for Jesse Washington

Patricia Bernstein, author of the First Waco Horror, detailing Elisabeth Freeman’s efforts to investigate the lynching of Jesse Washington sent this news: Jesse Washington marker installed February 12, 2023 In the photos: On the right, Shirley Bush, a cousin of Jesse Washington; Left, Nona Kirkpatrick, grand niece of Sank Majors, who was falsely accused of […]

Anti-Lynching in 1916

When Elisabeth Freeman showed her niece Ruthie (my mother) the scrapbook detailing her activism, she instructed her not to look at one section. “It was,” she said, “too terrible for a young girl.” * My mother ignored her warning but she was not wrong—there were gruesome images of the torture and lynching of a young […]